Research

Controlled density transport

The problem of controlling distributions of states has many applications, including uncertainty propagation and quantification, stochastic control and motion planning under uncertainty, controlled fluid transport, and control of distributed multiagent systems. In such problems, the distribution of states is modelled as a probability density function. The animations below illustrate this idea on a Duffing system. The left figure shows the time evolution of a single state in state space; the right figure shows the evolution of an ensemble of states, which are modelled as a probability density function.

To model the time evolution of density functions, we use ideas from the operator-theoretic view of dynamical systems. The Perron-Frobenius operator is the operator which propagates density functions forward in time under the flow of a dynamical system. This operator is the adjoint of the Koopman operator, which propagates observable functions along trajectories of a dynamical system. This relationship enables the use of data-driven methods, such as extended dynamic mode decomposition (EDMD) for constructing finite dimensional approximations of the operator.

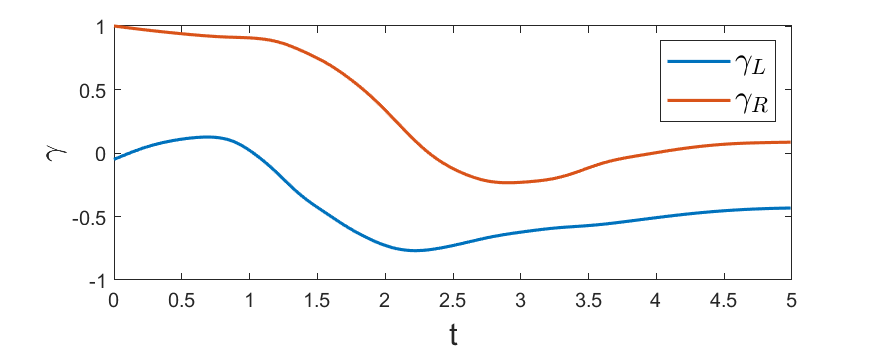

For a controlled dynamical system, this method yields a high-dimensional bilinear system for the density evolution. We solve an optimal control problem on this system to steer an initial distribution of states to a desired target. As an application, we consider the problem of a rotor-driven Stokes flow, where the torques on a pair of micro-rotors are controlled to manipulate a blob of fluid particles toward a target, as shown below. The plot on the right shows the optimal rotor torques of the left and right rotors over time.

For more details, see the following paper:

Controlled density transport using Perron Frobenius generators

J. Buzhardt, P. Tallapragada.

IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, 2023. Preprint

Rolling, Jumping Robot

Littlewood’s hopping hoop is a classic dynamics example, which consists of a lightweight hoop with a heavy eccentric mass. This simple mechanism is known to exhibit a hopping behavior when rolled fast on flat ground or from rest on an incline, as shown in the video below.

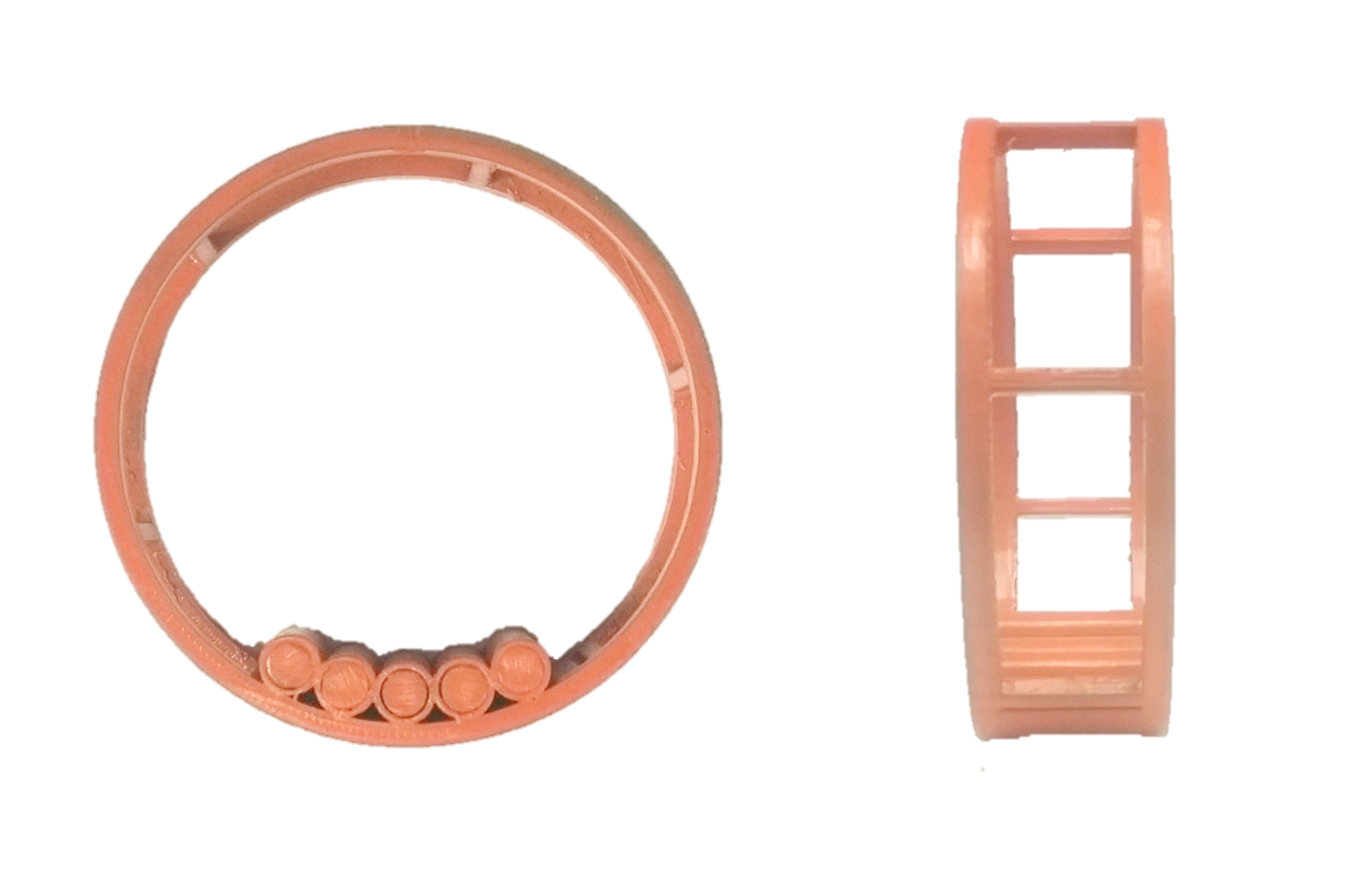

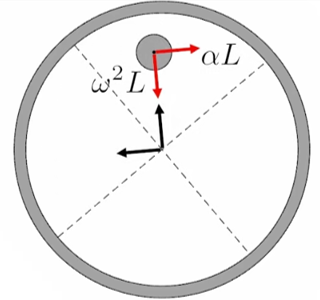

This hopping behaviour is due to a lifting effect on the hoop created by the large centripetal acceleration of the offset mass, as shown in the schematic above. Inspired by this, we design a robot to roll and jump from flat ground by actuating a heavy pendulum at high speed in order to jump. As shown in the video below, our robot is able to achieve vertical jumps of 2.4 body lengths.

Additionally, the robot can clear large horizontal distances while in air by achieving a high rolling velocity before initiating a jump. As shown in the video below, the robot clears over 6 body lengths in air and is able to achieve multiple jumps with minimal recovery time.

For more details, see the following papers:

A Pendulum-Driven Legless Rolling Jumping Robot

J. Buzhardt, P. Chivkula, P. Tallapragada.

IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2023 Preprint

A Passive Jumping Mechanism

P. Tallapragada, J. Buzhardt, R. Seney.

2019 Dynamic Systems and Control Conference (DSCC) ASME. October 2019. Paper Link | Preprint

Low Reynolds number swimming

Motion at zero Reynolds number is governed by the Stokes equations, where viscous effects are dominant relative to inertial effects. The linearity and time-independence of the Stokes equations also lead to a kinematic reversibility known as the Scallop theorem, which states that reciprocal motions of a body will not produce a net translation in a Stokes flow. This statement, gets its name from the idea that a scallop would not be able to swim in a low Reynolds number setting since it possesses only a single degree of freedom and is thus only capable of such reciprocal motions. This eliminates many aquatic locomotion strategies which are common at larger scales, such as periodic flapping or undulating. This also helps to explain the effectiveness of simple, continuous rotation for locomotion, as this does not suffer from the reciprocity described in the scallop theorem.

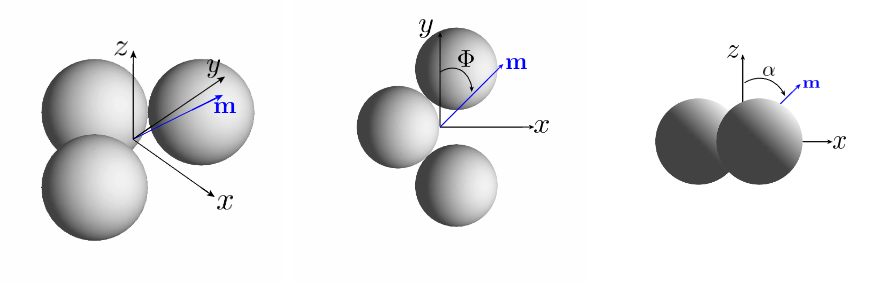

We study the motion of simple achiral swimmers composed of three rigidly connected spheres in a 90 degree bend, pictured below. This is one of the simplest geometries which can exhibit a net translation due to an applied torque, and thus can be driven by a torque induced through a periodically rotating magnetic field.

We develop a simulation strategy based on the Stokesian dynamics algorithm, which allows us to study the single swimmer motion, interacting groups of these swimmers, and the corresponding fluid velocity fields. The fluid velocity field produced by a single swimmer is shown below, when subjected to a periodically rotating magnetic field.

When two swimmers are present, hydrodynamic interactions due to this rotational velocity field leads to the swimmers taking helical trajectories as they spiral about one another, as shown in the animations below.

The same is true when a larger group of swimmers is present. The simulations below show the trajectories of a group of 16 interacting swimmers.

Additionally, these hydrodynamic interactions can be utilized to contactlessly manipulate a passive particle to drive it in a desired direction. This is demonstrated in the animation below. This control is achieved by switching the orientation and frequency of the applied magnetic field to alternatingly drive the swimmer and the particle.

For more details, see the following papers:

Dynamics of groups of magnetically driven artificial microswimmers

J. Buzhardt, P. Tallapragada.

Physical Review E 100, 033106 September 2019. Journal Link

Magnetically actuated artificial microswimmers as mobile microparticle manipulatorss

J. Buzhardt, P. Tallapragada.

ASME Letters in Dynamic Systems and Control, 1:1, January 2021. Journal Link

Offroad vehicle navigation

coming soon